“We are going to enter a booming economy. It's happening as we speak….I have little doubt that with excess savings, huge deficit spending, a new potential infrastructure bill, a successful vaccine, and the end of the pandemic will lead the U.S. economy to lightly boom, and this boom should run through 2023 because all of the spending could extend well into 2023.”

- JP Morgan Chase (JPM) CEO Jamie Dimon

Are we witnessing the long-awaited “great rotation”? Many are calling for it. Even more are thinking it. As interest rates rise, economic growth accelerates, and inflation percolates, a growing number of “value bulls” believe we are on the verge of a late 90’s-like situation where value/cyclical stocks thrive and high-priced growth stocks falter. While this is certainly possible, I have a feeling there will be more to this story.

Before we get to that, let’s first take a trip back in time.

Time Travel

In early 1989, the classic time travel film, Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, hit theatres nationwide. This cult classic tells the story of two delinquent friends who travel back in time in a phone booth to “collect” important historical figures for a high school history class presentation at San Dimas High. After rounding up Socrates, Abraham Lincoln, Beethoven, Joan of Arc, and for some reason Billy the Kid, Bill and Ted bring them back to the present day, trot them out on stage, and explain how each impacted society. The movie is ridiculous, but provides an interesting lens for how to think about today’s economy, otherwise known to many as “The Fourth Industrial Revolution”.

The Industrial Revolutions

Imagine that we could borrow Bill and Ted’s phone booth, but instead of using it for a high school history project, we use it to formulate an investment case today based on the three prior industrial revolutions.

Set the dial for the early part of the 19th century, the middle of the first industrial revolution. This period produced new technologies like the spinning wheel, steam engine, locomotive, telegraph, photograph, typewriter, and the modern factory. Throw a few in the phone booth. Now, set the dial for the 100 years later.

This period, the second industrial revolution, saw steel replace iron, electricity emerge, the telephone revolutionize communications, and the internal combustion engine change the way people traveled. Grab a few. Last stop….set the dial for the latter half of the 20th century.

The third industrial revolution brought us semiconductors, the mainframe, personal computing, and eventually the internet. Grab a few. Now head back to 2021. Time to present our our findings.

Industrial Perspective

In each of these revolutions, countless entrepreneurs failed, but those that succeeded transformed the world. In doing so, they were rewarded handsomely, as were their financial backers. The story does not end there though. These new technologies subsequently increased the speed and efficiency associated with industries like travel, communications, and manufacturing, all while reducing costs. They also created new industries, enabled novel companies to emerge, and kick started new ecosystems. This did not happen overnight, however. It took time for them to gain adoption and proliferate through the economy. Why? Because many consumers, customers, and businesses were initially skeptical that these new technologies would be upgrades on the current products of the day.

Others believed they would cause more harm than good.

Yet, despite the resistance, each industrial revolution ended up changing the course of history, and typically at an accelerating pace.

A Similar Path

As seen in the chart above, in each of the first three industrial revolutions the biggest beneficiaries shifted over time. In the early stages (1-2), gains accrued to those who pioneered and invested in these new technologies. In the middle stages (3-4), innovative companies emerged, lesser companies fell by the wayside, new ecosystems developed around the winners, and incumbent companies that most effectively adopted these new technologies thrived. In the latter stages (5-6), consumers became the biggest benefactors as these new technologies created goods and services that were finally affordable and accessible. A consequence of this pattern, however, was that the companies that pioneered these advances eventually saw their return-on-capital converge with their cost-of-capital, which led to a lower equity returns given the subsequent multiple compression.

Let’s take a look at how this pattern played out in reality.

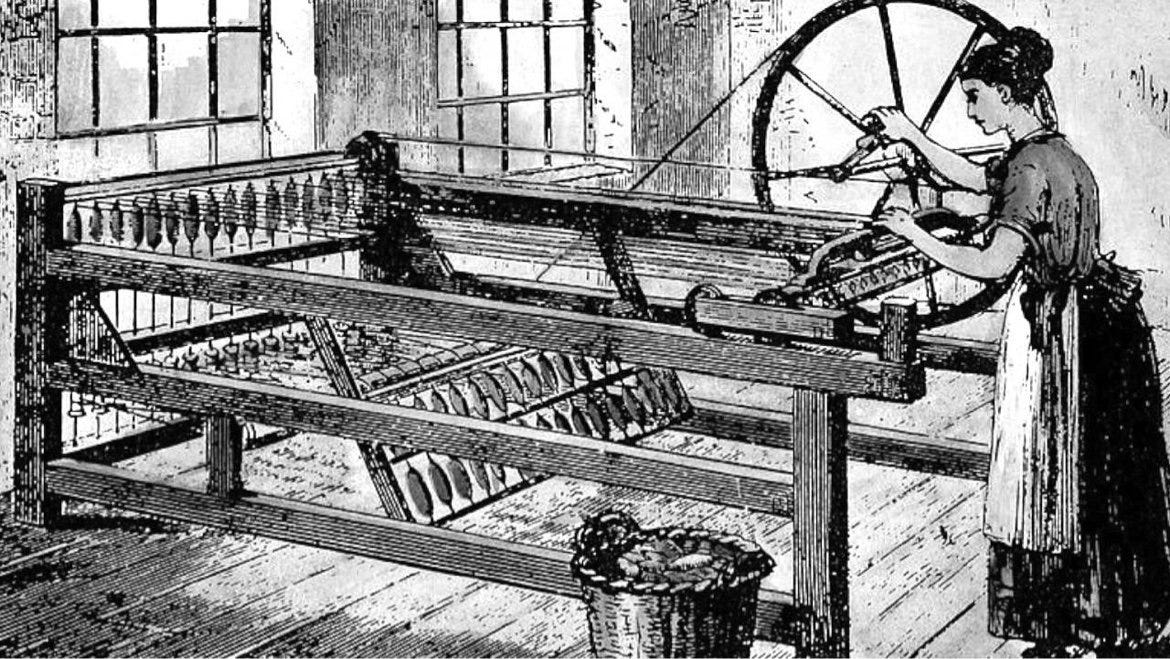

In the first industrial revolution, the advent of new technologies like the Spinning Jenny transformed the way clothes were produced as machines replaced human spinners.

This increased production by as much as ten-fold, significantly reduced costs for the companies that employed it, and eventually led to consumers being able to have more and better clothes.

The second industrial revolution introduced electricity, which enabled factories to operate longer hours and increase output, connected rural America with urban cities, increased entertainment options, and dramatically reduced risks associated with both darkness and gas lighting.

It also eventually led to new consumer products such as the automobile, washing machine, electric stoves, radio, televisions, and water pumps.

Semiconductors and personal computing in the third industrial revolution served as the foundation for the future advances in computers, telecommunications, and the internet, which created an entirely new economy as a largely physical reality has transformed into a digital one.

The 4th Industrial Revolution

This leads us to the 4th Industrial Revolution, which has been catalyzed by advances in technologies such as big data, mobile computing, the cloud, smart sensors, and biotechnology. While the foundation for these advances has been around for a while, the modern advancement began in earnest close to a decade ago. Unsurprisingly, investments in these technologies have recently been bearing fruit as evidenced by the outsized returns from venture capital and growth equity funds. The same can be said for the public equity markets where the performance gap between the growth and value indices is one of the widest on record.

So where does this leave the market today? If I had to guess, we are likely somewhere between stages 3 and 4 in the chart (increased demand and mass production). The fact is, technology companies have been thriving over the past decade (stages 1-2), which has been a direct result of selling more of their products and services to a new and growing subset of customers.

Logically, if customers are continuing to adopt these new technologies, they must be seeing them help generate higher revenues, increase productivity (lower costs), or a combination of the two. Otherwise, why would these customers continue to increase their orders? Talk to any executive who has seen travel expenditures fall due to Zoom meetings, waste reduced due to data analytics, and throughput increase as a result of digitization and mobile adoption, and it’s the most obvious conclusion. On the surface, these trends are obviously benefitting the tech sector. Dig a little deeper and it is hard to deny that these trends are also positive developments for both value investors and the economy as a whole.

Wrapping Up

Given that the S&P 500 has compounded at nearly 15% for the past ten years and valuations are on the high side, the consensus generally believes that public equity returns will be meaningfully lower than their long-term historic averages for the next 7-10 years (e.g., forecasts tend to range from 5-6% on U.S. equities to negative returns for perma-bear GMO). In my experience, given that the consensus is much more often wrong than right (see the “there is nothing on the horizon that could derail this market” sentiment back in late 2019…), I am having a hard time with this call. Throw in the fact that the S&P 500 has compounded at just 8.5% over the last twenty years (~2% lower than the long-term average) and I am downright skeptical.

With this as a backdrop, how might this current market unfold from here? After carrying the market for the better part of a decade, I could see a situation where growth stocks “hand the baton” over to value stocks as the latter generates better financial performance from adopting these new technologies, while also benefitting from tailwinds tied to better economic growth, higher interest rates, and a weaker dollar. At the same time, while there could be pockets of large price declines in the extremely expensive growth stocks (e.g., meme, software-as-a-service, and ESG-related stocks), I do not expect a repeat of the massive dot.com era broad-based decline in growth companies. Rather, it is more likely that they will just post more modest returns than we have become accustomed to, largely as a result of valuation compression. Lastly, keep an eye out for younger companies that adopt and leverage these technologies to forge new paths and address some of society’s biggest pain points today, much like Home Depot, Wal Mart, Apple, and Oracle did in the 1970s.

CASE STUDY:

The Value vs. Growth baton handoff during the Third Industrial Revolution

So why might value grab the baton from growth? Because it has happened before. Just look at the third industrial revolution. During the early part of this period (1959-1972), the Vanguard U.S. Growth fund (VWUSX) outperformed the Vanguard Windsor Value Fund (VWNDX) +970% to +300%. This outperformance was led by the “Nifty Fifty” and other growth stocks that included Dow Chemical, General Electric, McDonalds, Proctor Gamble, Xerox, and Black & Decker. Then from 1973-1988, the performance flipped as the Windsor Value Fund returned +820% vs. +225% for the U.S. Growth Fund. In the 70s and 80s, the value fund was led by the energy, real estate, and materials sectors, while many of the Nifty Fifty constituents continued to execute at a business level, their valuations contracted meaningfully during this period. While the same data is not as easily accessible for the 1st and 2nd industrial revolutions, if I had to guess, a similar pattern would have emerged.