THE “ACCESS” MYTH

As I said in my last post, growth is intoxicating, technology fuels the economy, and the power law — where a few standout investments deliver outsized returns — dominates the venture capital ecosystem.

Naturally, everyone wants a “piece of the action” — namely, a stake in elite venture funds like Sequoia or Andreessen Horowitz and the chance to own the next Airbnb, Uber, Snowflake, or Coinbase.

But here is the catch: like an exclusive club, these elite funds are closed to most investors. Meanwhile, their portfolio companies are staying private longer, keeping the big public winners out of reach. As a result, many investors feel like they are missing out and disadvantaged.

Or so the story goes.

But, what if I told you this story is wrong? What if I told you the opportunity to invest in these companies is available to all investors — often at better prices and valuations than even the top venture capitalists paid?

The Way it Used To Be

It wasn’t always this difficult to “get in on the ground floor”. Companies like Amazon, Apple and Microsoft went public at modest market capitalizations. Amazon IPO’d in 1997 at $500 million (~$940 million in today’s dollars), Apple’s 1980 IPO valued it at $1.2 billion (roughly $4.6 billion today), and Microsoft’s 1986 debut came in at $520 million (~$1.5 billion today). As a result, public market investors could have purchased these companies as small caps and ridden their growth into the stratosphere, turning a few thousand dollars into millions.

Fast forward to today, and many feel like the game is rigged. Companies like Airbnb ($50 billion IPO), Uber ($85 billion), Snowflake ($70 billion), and Coinbase ($60 billion) went public at values that automatically placed them in the large cap category, with most of their growth captured exclusively by private investors.

So, the question is, without access to the Sequoia’s or Andreessen’s of the world, is the typical investor simply “out of luck”?

The Truth Hiding in Plain Sight

Investors are far from “out of luck.”

Why?

Because the public markets are anything but a barren wasteland. In fact, they are more like buried treasure, so long as you know where to dig.

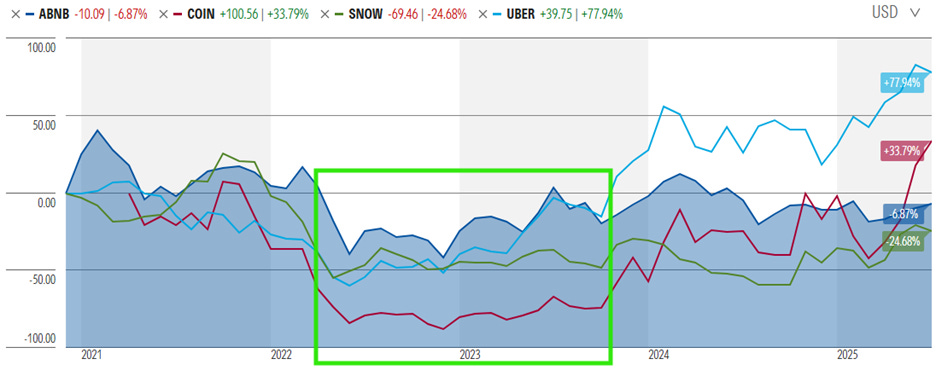

After IPO’ing, companies like Airbnb, Uber, Snowflake, and Coinbase saw their stock prices crater, often selling below their IPO valuations, and even their later-stage venture rounds. Take Airbnb: after its 2020 debut, it plummeted over 40% to a $30 billion market cap in 2022. Uber and Snowflake each dropped more than 50%, and Coinbase? It collapsed nearly 90%, offering entry points cheaper than what many venture capitalists paid in private rounds (Airbnb traded as low as 6x sales versus more than 10x at IPO, Uber at 1.6x versus more than 7x at IPO, Snowflake at 20x versus more than 260x, and Coinbase at 1.5x versus 39x.)

5-Year Stock Price Performance

Airbnb, Coinbase, Snowflake, Uber

Now, you might be thinking this was an isolated case. But, what if I told you this is the furthest thing from a new phenomenon?

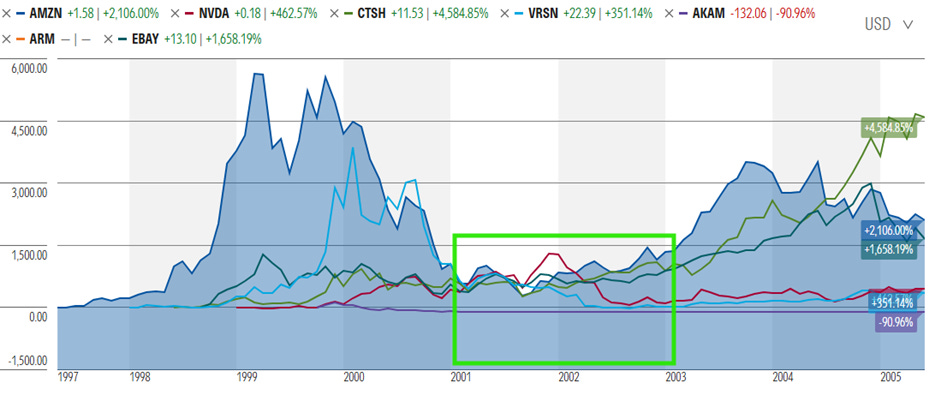

Look no further than Amazon. Its 1997 IPO valued the company at 30x price-to-sales. In the years that followed, its market cap would irrationally rise north of $30 billion, which equated to a 2,000x price-to-sales ratio. Then, in 2001 when the dot.com crash occurred, Amazon’s stock fell more than 90% despite revenues having surged more than 20,000% from $15 million to over $3 billion in just five years. The price-to-sales ratio at the bottom? Just 1.2x.

Amazon Stock Price Performance (1997 - 2002)

Companies like eBay, Nvidia, and Akamai followed similar paths — skyrocketing post-IPO, then falling materially, giving patient public market investors plenty of chances to buy at great entry points.

Select Venture-Backed Stocks Performance (1997-2005)

The Catch (There is Always One)

Sounds simple, right?

Of course not.

For every Amazon or eBay, there is a graveyard filled with Webvans, Pets.com, and Globe.com — companies that promised the moon and delivered nothing.

This is where the power law comes into play because while it gets a lot of press in the private markets, it is also alive and well in the public markets.

If so, how can a public market investor execute on it?

You don’t need to be a genius. In fact, far from one. You just need to take a page out of John Templeton’s book.

In 1939, with the world reeling from the Great Depression and the start of World War II, Templeton bought one hundred shares of every stock trading under $1 (skipping those in bankruptcy.) While some went to zero, others soared 10x or more as the economy improved as a result of the war’s mobilization. Within four years, Templeton had quadrupled his money.

A Playbook for the Rest of Us

Despite the fact that Templeton employed his strategy of buying a large swath of beaten down stocks more than three-quarters of a century ago, it is still actionable to this day, albeit in a slightly different form.

This means that instead of chasing exclusive venture funds with their 2-and-20 fee structures or settling for mediocre ones when this pursuit fails, many investors are likely better off building a list of public venture-backed companies — preferably ones originally backed by top-tier firms like Sequoia or Andreessen — that have experienced significant selloffs in the public markets. Then if (and when) they eventually reach reasonable valuations, investors should buy them with the intention of holding them for a decade or more to enable the power law to work its magic.

While success is certainly not guaranteed, I am willing to bet this approach would end up with a better outcome than most of the funds that are willing to give you access. After all, it is not about picking the next unicorn with precision; it is about stacking the odds in your favor and giving the eventual winners the time to do the heavy lifting.