Ever heard of Bob Kierlin? I hadn’t either until I came across his name in the obituary section of the Wall Street Journal.

The reason Kierlin’s passing was covered was because he founded a company that produced what is commonly referred to as a “hundred bagger,” which means that an investment in its initial public offering (“IPO”) would we worth at least 100 times your intital investment.

So, what kind of company did Kierlin found?

A high growth, venture-backed software company?

An artificial intelligence startup?

A biotech with a blockbuster drug?

Fartcoin?

Not exactly.

Kierlin founded Fastenal, a company that produces and distributes bolts, screws, studs, washers, and you guessed it, fasteners.

That’s right. Those tiny things you use anytime you put together a piece of IKEA furniture, fix a lawnmower, or assemble a toy at 2am on Christmas Eve.

Learning that this Midwest-based company selling small industrial parts generated a hundred bagger got me thinking — is Fastenal an outlier, or are there other companies with similar profiles that have done just as well?

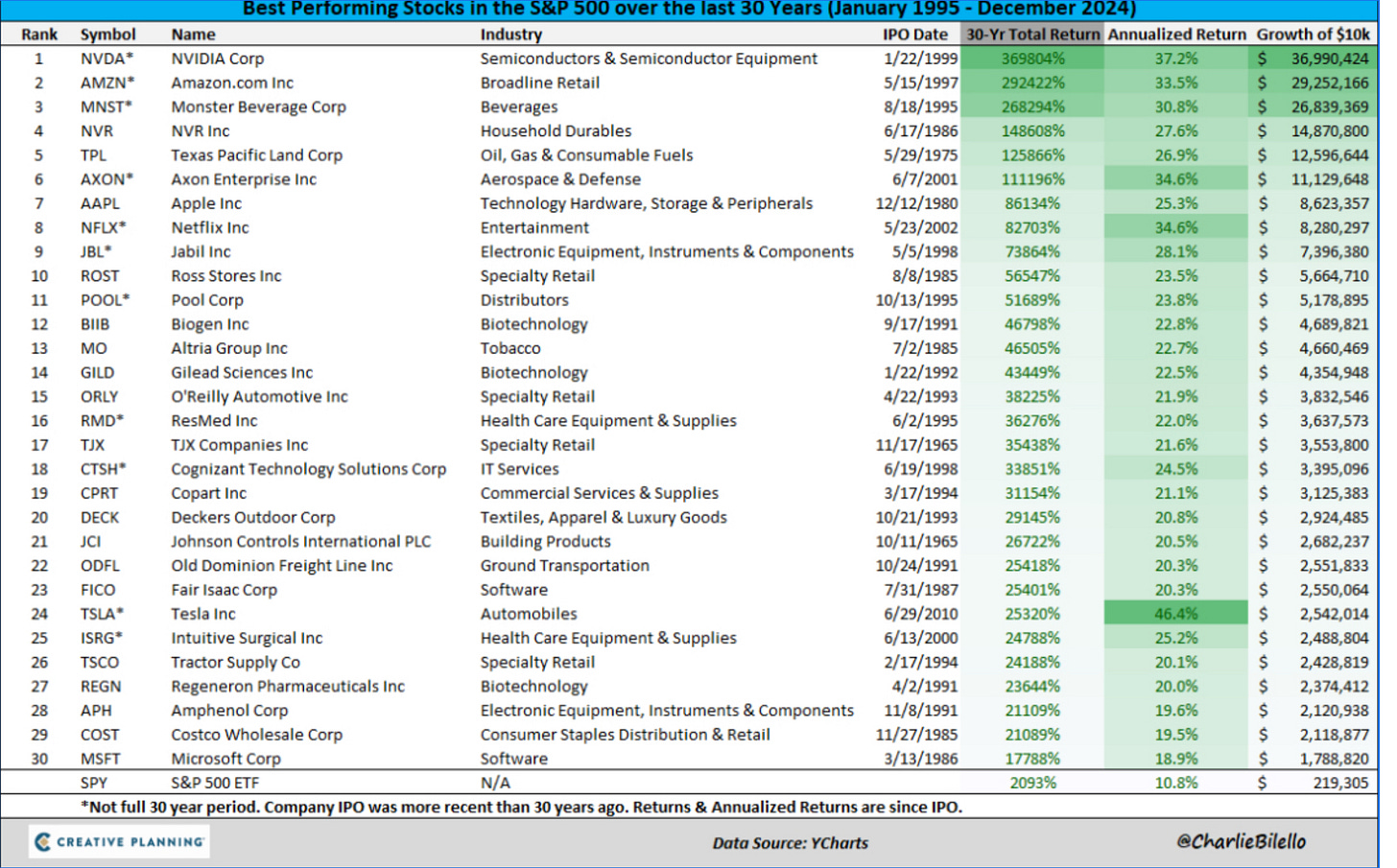

To check, I looked up the best performing companies over the past three decades.

Care to guess a few that made the list?

If you said companies like Nvidia, Amazon, Netflix, and Apple, you would be right — they finished #1, #2, #7, and #8.

But how about Monster Beverage, NVR, or Texas Pacific Land? What about Axon, Jabil, or the super exciting retailer, Ross Stores?

I’m guessing these companies were not on your bingo card. Yet, they finished #3, #4, #5, #6, #9, and #10.

The story doesn’t end there, as other surprising winners included Pool Corp, Altria, O’Reilly, TJX, Deckers, Johnson Controls, Fair Issac, Old Dominon Freight, and Tractor Supply.

So, why have these little-known companies been so successful?

In large part because they are boring.

Boring?

Yes, boring.

But, who wants to invest in boring businesses when you can invest in exciting businesses redefining the future?

The answer is investors who prefer consistency and predictability over excitement and the unknown. Investors willing to be patient. Those who care more about a company’s durability than its potential to define the future.

This is harder than it looks.

Why?

Because when something is exciting, people want to be a part of it. When people want to be a part of it, it garners a lot of attention. When it garners attention, talent and capital flow to it. When talent and capital flow to it, competition increases. When competition increases, dramatic innovation occurs, disruption takes place, revenue gets divided up, and margins compress.

This is great for the economy because growth and innovation are force multipliers of economic growth (examples include the laying of fiber optic cables during the dot.com boom, shale gas production during the 2010’s, and data centers and semiconductor chips for artificial intelligence today). However, this typically isn’t great for shareholders, especially when expectations and valuations rise in response to this excitement.

Then what should investors want?

Boring businesses.

Why?

Because when something is boring, few people want to be a part of it. When few people want to be a part of it, talent and capital avoid it. When talent and capital avoid it, competition is limited. When competition is limited, innovation is slower, disruption is non-existent, and incumbents can steadily increase their revenues and maintain their margins.

Now, I want to be clear, and this is important. This is not to say that these boring businesses do not innovate. They do, but at their own pace. This means innovating as opportunities present themselves, as opposed to doing so for fear of falling behind (like the hyperscalers are doing right now).

Look no further than Fastenal. Has it innovated? You bet, but by steadily expanding its product offerings, introducing vending solutions, and streamlining its supply chain in a measured, efficient, and cost effective way.

The same could be said for the homebuilder NVR, which has innovated by employing an asset-light model (i.e., by not acquiring land before building), improving operational efficiencies, and vertically integrating the company.

Or, like the manufacturing company Jabil has done through improving supply chain analytics and automating workflow to improve efficiency.

Even Tractor Supply has innovated in remarkable ways by utilizing technology to better recommend products to customers, improve the check-out experience, enhance pricing, and increase product offerings.

Why is this so important?

Because history has shown that extreme competition, over-investment, and hype has often caused high growth technology companies to flame out, while boring businesses have hung around for very long periods of time due to low levels of competition, a lack of investment, and practically zero hype.

Just look at the fifteen companies I mentioned earlier — one was founded in the 1990s (Axon), four in the 1970’s or early 1980’s (Deckers, Pool Corp, NVR, and TJX), four in the 1950’s or 1960’s (Ross Stores, O’Reilly, Jabil, and Fair Isaac), three in the 1930’s (Old Dominion Freight, Tractor Supply, and Monster Beverage), and the last three prior to 1900 (Texas Pacific Land, Altria, and Johnson Controls)!

These days we live in a world in which being boring often makes you overlooked at best, or shunned at worst. Colleges want applicants to be the antithesis of boring. Harvard says as much right on their admissions homepage,

“We are looking for students with special talents or excellence of all kinds, perspectives formed by unusual personal circumstances.”

Young athletes have been led to believe that in order to stand out they need to specialize, make the flashy play over the routine one, and create highlight tapes. Musicians, scientists, and artists are told something similar.

Don’t get me wrong. It is incredibly important for America to have talented people at universities, animated and high IQ young people starting companies, dynamic CEOs leading them, and hungry young people wanting to work for them. I also believe that many walks of life require incredibly talented specialists. After all, if I tear a ligament in my knee, I would much prefer a surgeon who exclusively repairs knees over one who also does hips, wrists, shoulders, and elbows.

However this has its limits.

Could Harvard be better off with classes that consist of students with “special talents and unusual circumstances,” as well as those who are considered “boring” by some, but well-rounded, multi-disciplinary, and “inch deep and mile wide” by others?

Are teams more successful if they have a mix of flashy stars and “glue guys”?

Are symphonies, scientific research organizations, and art galleries better off and more interesting if they possess a blend of talent?

I sure think so.

The same goes for investors and portfolio management.

Should a portfolio have high-flying growth investments?

Sure.

Just look at how the Nasdaq has done over the past decade (annualized return of ~18% vs. ~13% for the S&P 500 and 8.5% for the U.S. Value Index). Yet, when a portfolio gets over-allocated to these types of high growth businesses, especially when the hype, competition, and capital invested reaches a fever pitch, more balance is typically needed.

It currently feels like we might be experiencing one of those moments. If so, these are the times that “boring businesses” can be a beautiful thing.

Oh, and if you’re curious, Fastenal IPO’d in the late 1980’s, a year after a young technology company named Microsoft went public. Care to guess which has outperformed over the past ~40 years?

FASTENAL vs. MICROSOFT

Stock Performance Since IPO’s in Late 1980’s

Great job Teddy, love you work!

Among the most memorable interview questions I've been asked was, "Are you a racehorse or a workhorse?"