Growing up, March Madness was magical. I remember exactly where I was in 1992 when Christian Laettner hit the game-winning mid-range jumper against Kentucky after a baseline heave from Grant Hill. I can vividly recall watching Princeton upset UCLA with a vintage Pete Carril back-door pass, Chris Webber call a timeout he didn’t have against UNC, Bryce Drew drain a legendary three-pointer for Valpo against Ole Miss, and a little known freshman point guard from Santa Clara named Steve Nash orchestrate an upset of #2 ranked Arizona.

Sadly, much of this magic has faded. In fact, as this years’ tournament tipped off, I realized I didn’t know the name of a single player other than Duke’s freshman superstar, Cooper Flagg.

Now, this might be because I’m in my mid-forties, spend most weekends with my family instead of watching sports like I did in my twenties, and because UVA (my Alma Mater and architects of the greatest comeback story in sports history…shameless plug) missed the tournament.

Yet, I think we all know that’s not “it”.

In fact, I think we all know what the “it” is — NIL and the Transfer Portal.

Together, the two have made college basketball unrecognizable.

Players switch schools as if they are changing into a new pair of Nikes, chase dollars instead of titles, and have little allegiance to the University they represent. In doing so, the idea of being a student-athlete has become a farce.

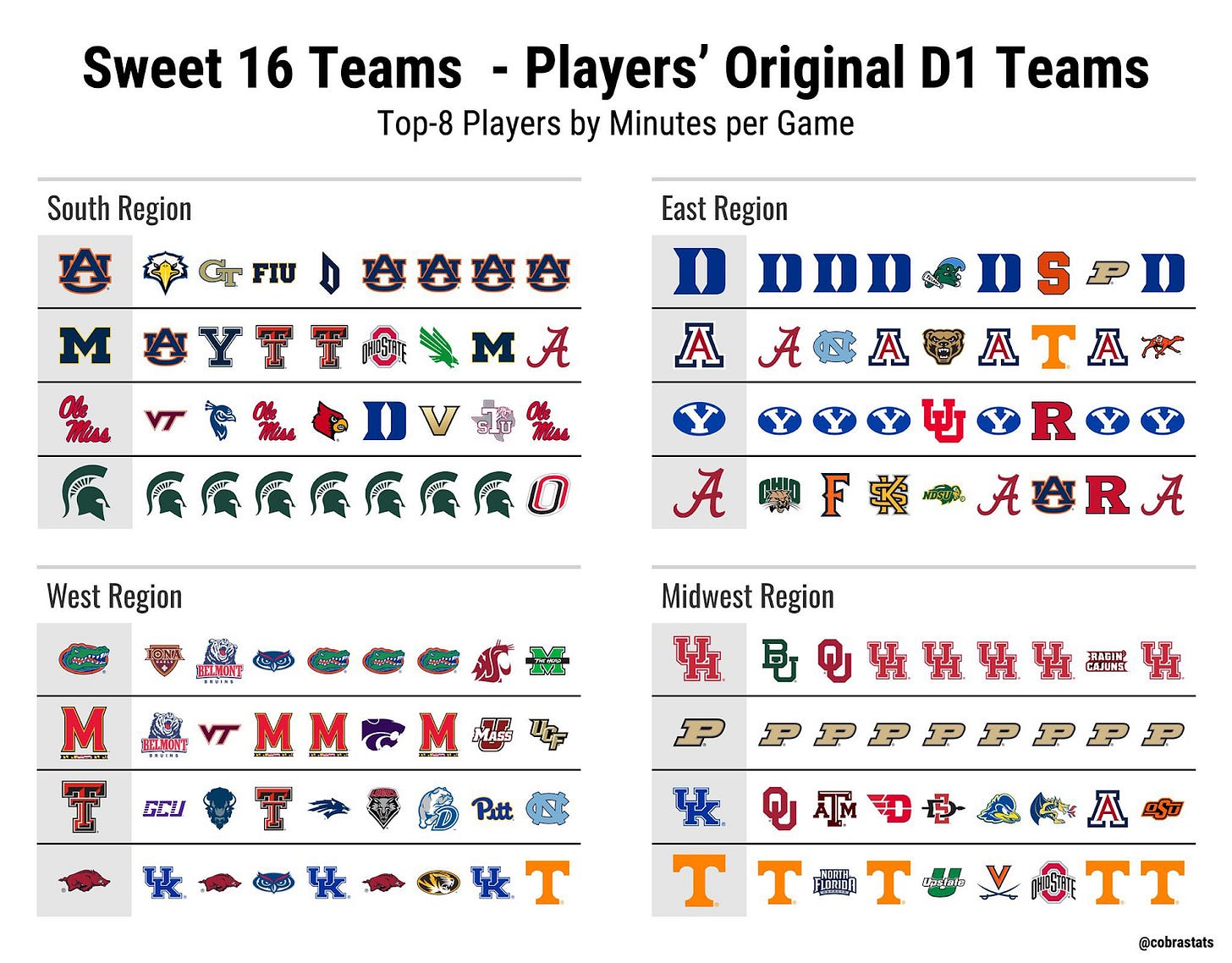

Just look at this chart showing where each Sweet Sixteen team’s top eight players started their college careers.

As a result, we might be at risk of losing what made the tournament special — mid-majors knocking off top seeds, upperclassmen who have paid their dues stepping into leading roles, and legends like Jim Boeheim, Roy Williams, Coach K, and Tony Bennett roaming the sidelines.

Additionally, as Jim Calipari recently highlighted,

“There are kids in the United States that are freshmen who deserve scholarships to college and aren’t getting them. We’re all waiting for transfers. That is what disappoints me the most.”

Should we be surprised?

Of course not, especially when you consider the issue of tradeoffs.

What did we think was going to happen when college sports started being broadcast from sunrise until late into the night across endless networks?

What did we expect would happen when universities raked in tens of millions of dollars, while the players were left with so little?

We were living in a world where a lot of people thought they could have their cake and eat it too.

And herein lies the problem with tradeoffs — People gladly accept short-term benefits of something when it is happening, but rarely consider the long-term consequences.

Taking medicine when we are sick might make us feel better in the moment, but we rarely consider the potential side effects. Drinking alcohol can make a night out more fun, but a hangover is the tradeoff. Investing in private equity might generate higher returns, but it comes with more illiquidity, complexity, and inflexibility.

The same goes for college athletics.

Things should feel pretty good today. Fans have more access to college sports than ever before, universities are generating unimaginable sums of money, and players finally have the freedom to play wherever they want, for whomever they want, and get paid hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of dollars to do so.

Yet, something feels off.

But why?

Because it feels like the painful part of this tradeoff is just beginning to emerge.

Ben Carlson, of Ritholtz Wealth and the blog “A Wealth of Common Sense,” posted this excerpt from comedian Steve Martin’s autobiography in which he talks about his life after becoming the most popular stand-up comic in the country.

“Though the audiences continued to grow, I experienced a concomitant depression caused by exhaustion and isolation. As I was too famous to go outdoors without a discomforting hoopla, my romantic interludes ceased because I no longer had normal access to civilized life. The hour and a half I spent performing was still fun, but there were no band members, no others onstage, and after the show, I took a solitary ride back to the hotel, where I was speedily escorted by security across the lobby. A key went in a door, and boom: the blunt interior of a hotel room. Nowhere to look but inward. I am sure there were a hundred solutions. I could have invited friends to join me on the road, or asked a feel-good guru to shake my shoulders and say, ‘Perk up, you idiot,’ but I was too exhausted to communicate, and it seemed like a near-coma was the best way to spend the day. This was, as the cliche goes, the loneliest period of my life.”

So, what does a comic on tour have to do with college athletes?

A lot actually.

As great as things appear to be on the surface for college athletes today given how much money they are making, I wouldn’t be surprised if in a few years, we hear them echo a similar sentiment.

Why?

Because if you ask any athlete at the end of their career what the best part of it was, they almost universally talk about the teams they played on and the people they played with.

All you have to do is watch the “30 on 30” about the 1983 NC State National Championship Team, the documentary titled “The Class that Saved Coach K” about Mike Krzyzewski’s first recruiting class, or the ESPN special, “Unbelievable”, that profiles UVA’s improbable path to the 2019 title.

My favorite though?

Boston College senior Dennis Clifford choking back tears after being knocked out of the 2016 NCAA tournament when asked a question about what his best memory would be about playing college basketball,

“Going out to eat (with my teammates)”

Players gush about their teams, their coaches, the life lessons they learned, and how deeply these experiences impacted their lives.

Now contrast this with how Maryland’s star freshman, Derik Queen, responded to a question after hitting the game winning shot against Colorado State in the second round about what his coach, Kevin Willard, has meant to him.

“He do pays us the money, so we gotta listen to him.”

While this response was surprising in the moment, in hindsight it shouldn’t have been because it was later revealed that at the time of this press conference, Willard was in the midst of negotiations to become Villanova’s new coach, despite Maryland being headed to the Sweet Sixteen (a week later after getting blown out by Florida, Willard resigned to his team over Zoom instead of in person.)

You can’t make this stuff up.

It’s hard to believe how much things have changed, but considering the system went from being overregulated to devoid of any rules practically overnight, it really shouldn’t be.

It’s akin to eating a pizza. Do it slice by slice over an hour and you’ll be fine. Do it in five minutes and you’ll have massive indigestion. College athletics is currently experiencing the latter.

So, where do things go from here?

Sadly, there is no going back, but I am not sure we should. The fact is progress is bumpy. It’s uneven. It’s full of overreaches and mistakes, but one thing history has shown is that retreating is rarely the best path ahead.

Yet, I think there is an opportunity. An opportunity for coaches and programs to strike a balance. To be innovators. To pivot in a different direction.

At the same time, there is an opportunity for players as well. For those who have the right mindset and understanding of what it means to be different. To have an “old school” streak.

But, what does this look like?

With few-to-no examples in college athletics, I would start by taking a page out of some of this country’s best companies’ playbooks…companies that have displayed an ability to innovate and change with the times, while maintaining a strong culture.

Look no further than Danaher, a more than forty-year-old company that was founded by Steve and Mitch Rales.

While Danaher started out focused on the industrial sector and thrived acquiring and improving companies largely tied to manufacturing, it evolved over time with the economy into a dynamic healthcare, life science, and technology-focused company. In the process, it has grown into $150 billion market capitalization.

The question is how?

In short, by placing a high priority on flexibility, culture, and a dedication to “Kaizen,” which is a Japanese word that stands for continuous improvement.

The key, as Mitch Rales said on a podcast last year, is that continuous improvement starts and ends with your people. More specifically, having the right balance of internal and external talent.

“It all starts with talent development and acquisition. We have a process inside Danaher where we would like 75% of our hires to come from within, self-promotion from within the enterprise. These are people who understand our DNA, understand our culture, and we want to reward them in their careers for doing great work. So, what's the best way to do that? We mentor, develop, and work with people to try to help them improve their livelihood (i.e., compensation and otherwise) through career development. However, we need to go outside for 25% because you need that outside thought process. We don't believe we know everything within. Once you become 100% inward thinking, the beginning of the end will start to take place. We need that outside thought process, fresh thinking.”

Given Danaher has compounded at close to 20% for more than four decades (versus 10.5% for the S&P 500) and that many of its employees have been rewarded by being shareholders themselves, I think Rales is onto something.

College coaches and athletic departments have a chance to do something similar. To be creative, proactive, and unique in the world of college athletics.

Instead of up-front cash payments, consider “equitizing” the program and giving shares to players that vest over time. Reward those who stick around, and occasionally go find a transfer, but only when that person brings something unique to the team. Sell a vision where if a player stays three or four years, gets a degree, and becomes part of the community and ambassadors for the program and university, they will be rewarded for many years to come, both from the equity they’ve accumulated, as well as the degree they have earned.

As an alum and former player, I’d certainly rather give money to a program that’s encouraging a model like this over a “pass the hat” model to pay players who are able to walk out the door at the end of each season to pursue the highest bidder.

This won’t be a fit for all players. Some, like Cooper Flagg, might be pro-ready (but imagine the legend he could become if he decided to stay three or four years, graduate, and accumulate “Duke equity” along the way.) Others simply won’t appreciate taking such a long view. Many will prefer the upfront cash, while scoffing at the soft stuff like the value of teammates, mentorship, and even graduating with an education and a degree.

Sound like a long shot?

Maybe, but here’s the key. You don’t need all players to be interested in this model to make it work. You just need the right ones. And for those select few who can see the value in such a model, they will be the ones who can actually have their cake and eat it too.

Unlike Steve Martin, these players won’t end up rich and lonely. Instead, like Valvano’s, Coach K’s, or Tony Bennett’s players, they will have memories and relationships that last a lifetime, all while having equity in an asset with a massive long-term financial runway.

If you need an image to bring this home, there is a scene in the movie “Air” where a small upstart company is the long shot to land Michael Jordan coming out of college. The big boys, Adidas and Converse, pitched money and stature, while Nike led with a vision. A vision for what could be if he signed with them. A path that wouldn’t be easy, but certainly rewarding. Sonny Vacaro (Matt Damon’s character) says to Jordan and his parents, in short,

“Money can buy you almost anything in life, but it can’t buy you immortality. That you have to earn. I am going to look you in the eyes and tell you the future. You were cut from your high school basketball team. You willed your way to the NBA. You are going to win championships. It is an American story and that’s why Americans are gonna love it. People are gonna build you up because when you’re great and new, we love you. You’re gonna change the fucking world. But you know what, once they build you as high as they possibly can, they are gonna tear you back down. That’s how it works, and we do it again and again and again. Now I am going to tell you the truth. You are gonna be attacked, betrayed, exposed, and humiliated and you will survive that. A lot of people climb that mountain, but it's the way down that breaks them because that’s the moment when you’re truly alone and what will you do then? Who are you, Michael? That will be the defining question of your life.”

This logic surrounding life’s “mountain” doesn’t just apply to the all-time greats. It applies to all athletes. The difference is that the path never looks the same. This said, traversing it is a lot easier if you’ve got great teammates, coaches, and lastly, an education and degree, to lean on. This is especially the case for the vast majority of athletes who don’t make it to the top.

As it relates to this year’s tournament (and potentially the future of college athletics), I have one final question. Remember that chart I showed you earlier? The one showing where each of the Sweet Sixteen’s top eight players started their careers?

Go back and look at the teams that reached the Final Four — Duke, Houston, Auburn, and Florida. On average, more than half these players started their careers at these schools, with the many of the rest being complementary transfers (mostly grad transfers or upperclassmen). Meanwhile, the twelve teams that got knocked out were either filled with rosters that were nearly entirely transfers (i.e., Michigan, Kentucky, and Ole Miss) or exclusively reliant on “home grown talent” like Purdue and Michigan State. In short, like Danaher, the most “balanced teams” have advanced the furthest.

Maybe this is a sign of things to come. Or maybe I am just a dinosaur grasping to the past.

I just took a tour of Cameron Indoor Stadium (Duke) and the tour guide pointed out that one of the requirements for having your Jersey retired was to have spent your entire basketball career at Duke. She pointed out that it may be a long time before they see another retired jersey in the age of NIL. (Upon further research, it's apparently not an official requirement, but an implied one.)

Nailed it, again. Chris and I were just talking about this last night - we miss the Cinderella stories (except when they involve a 1-16 upset), and following our favorite players for years who have a passion for their program. I think your idea of “equitizing” players makes a lot of sense and I can see a path toward implementing that where both players and schools benefit.

As always - great and thought-provoking read and I’m forwarding on…